Youtuber The Kavernacle mainly makes social commentary, media analysis, and political videos. Occasionally he comments on history, and often makes mistakes. This video demonstrates The Kavernacle is bad at history. See here for a written form of the arguments in the video, and here to see how The Kavernacle misunderstands cyberpunk.

Addlakha, Renu. “Discursive and Institutional Intersections: Women, Health and Law in Modern India.” International Review of Sociology 24.3 (2014): 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2014.954327.

Alghamdi, Malak A., Janine M. Ziermann, and Rui Diogo. “An Untold Story: The Important Contributions of Muslim Scholars for the Understanding of Human Anatomy.” The Anatomical Record 300.6 (2017): 986–1008. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.23523.

Agobard. Agobardi Lugdunensis Opera omnia. Edited by L. Van Acker. Corpus Christianorum. Turnholti [Turnhout, Belgium]: Typographi Brepols, 1981.

Arnold, David. “Burning Issues: Cremation and Incineration in Modern India.” N.T.M. 24.4 (2016): 393–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00048-017-0158-7.

Banerjee, Jacqueline. “Cultural Imperialism or Rescue? The British and Suttee.” The Victorian Web, 26 July 2014. https://victorianweb.org/history/empire/india/suttee.html.

Bose, Rakhi. “Dear Amish Tripathi, You’re Wrong. Sati Was Never Just a ‘Minor Practice’ in India.” News18, 31 October 2018. https://www.news18.com/news/buzz/dear-amish-tripathi-youre-wrong-sati-was-never-just-a-minor-practice-in-india-1924843.html.

Carey, Patrick W., and Joseph Lienhard. Biographical Dictionary of Christian Theologians. Bloomsbury Academic, 2000.

Coatsworth, John, Juan Cole, Michael P. Hanagan, Peter C. Perdue, Charles Tilly, and Louise Tilly. “Expansion, Reform, and Communication in the Agrarian Empires of Asia.” Global Connections: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. Vol. II. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Colish, Marcia L. The Stoic Tradition from Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages, Volume 1. Stoicism in Classical Latin Literature. Studies in the History of Christian Traditions Ser. Boston: BRILL, 1990. https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/PublicFullRecord.aspx?p=6943601.

Das Acevedo, Deepa. “Changing the Subject of Sati.” PoLAR 43.1 (2020): 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/plar.12354.

Given-Wilson, Chris. Chronicles: The Writing of History in Medieval England. London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007.

Grant, Edward. God and Reason in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Hassan, Mohammad Hannan. “Where Were the Jews in the Development of Sciences in Medieval Islam? A Quantitative Analysis of Two Medieval Muslim Biographical Notices.” Hebrew Union College Annual 81 (2010): 105–26.

Hansson, Sven Ove. “Introduction.” Technology and Mathematics: Philosophical and Historical Investigations. Edited by Sven Ove Hansson. Vol. 30 of Philosophy of Engineering and Technology. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93779-3, http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-93779-3.

Haq, Imran, and Humayun A. Khatib. “Light through the Dark Ages: The Arabist Contribution to Western Ophthalmology.” Oman J Ophthalmol 5.2 (2012): 75–78. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-620X.99367.

Hill, Jonathan. Dictionary of Theologians: To 1308. James Clarke & Company Limited, 2010.

Iqbal, Muzaffar. “Islam and Modern Science: Formulating the Questions.” Islamic Studies 39.4 (2000): 517–70.

Islam, Arshad. “The Contribution of Muslims to Science during the Middle Abbasid Period (750-945).” Revelation and Science 1.01 (2011).

Islam, Jaan. “Understanding Christian–Muslim Scholarly Cooperation under ‘Abbāsid Rule from 800–1000 CE.” Journal of Early Christian History 7.1 (2017): 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/2222582X.2017.1321966.

Jayan, Jayasree K., and K. C. Sankaranarayanan. “Divine Gender Inequality: A Study of Mythological Degradation of Hindu Women in India.” SSRN Journal (2017). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2949781, http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=2949781.

John S. P. Tatlock. “Some Mediaeval Cases of Blood-Rain.” Classical Philology 9.4 (1014): 442.

Kelly, Stephen. “The Pre-Reformation Landscape.” The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern English Literature and Religion. Edited by Andrew Hiscock and Helen Wilcox. First edition. Oxford Handbooks. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Leslie, Julia. “Book Reviews : Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial India, by Lata Mani, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1998. Pp. Xiv + 246.” South Asia Research 19.2 (1999): 196–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/026272809901900207.

Major, Andrea. “A Question of Rites? Perspectives on the Colonial Encounter with Sati.” History Compass 4.5 (2006): 780–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-0542.2006.00348.x.

———. “‘ETERNAL FLAMES’: SUICIDE, SINFULNESS AND INSANITY IN ‘WESTERN’ CONSTRUCTIONS OF SATI, 1500–1830.” International Journal of Asian Studies 1.2 (2004): 247–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479591404000233.

Mandal, Md. Abikul. “Critique of Social and Political Reforms of Raja Ram Mohan Roy.” Colonial Origins Of Modernity In India: Society, Polity and Culture. Edited by Keshab Chandra Ghosh and Sagar Simlandy. BFC Publications, 2022.

Mani, Lata. Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial India. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998.

McManus, Sean. “Do Atheists Need a Church of Their Own? — New York Magazine – Nymag.” New York Magazine, 18 April 2008. https://nymag.com/news/features/46214/.

Metzger, Bruce M. The Bible in Translation: Ancient and English Versions. Baker Academic, 2001.

Pincince, John. “Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial India (Review).” Journal of World History 12 (2001): 505–8. https://doi.org/10.1353/jwh.2001.0037.

Sawant, Nitin. “Raja Ram Mohun Roy – Indian Reformer or British Stooge?” Hindu Dvesha, 29 February 2024. https://stophindudvesha.org/raja-ram-mohun-roy-indian-reformer-or-british-stooge/.

Scott, Nicole. “Richard Dawkins and Me in Dubai | Free Inquiry.” Free Inquiry 42.3 (2022). https://secularhumanism.org/2022/04/richard-dawkins-and-me-in-dubai/.

Sen, Sudipta. “Sovereignty and Social Reform in India: British Colonialism and the Campaign Against Sati, 1830–1860 by Andrea Major (Review).” Victorian Studies 56.3 (2014): 525–26.

Sethy, Prabira, and Raj Kumar, eds. “Remembering Social Reformer Raja Ram Mohan Roy’s Perspective on Women.” Indian Journal of Social Enquiry 9.2 (2017): 51–63.

Soman, Priya. “Raja Ram Mohan Roy and the Abolition of Sati System in India.” International Journal of Humanities, Art and Social Studies 1.2 (2018).

Stone, Linda, and Caroline James. “Dowry, Bride-Burning, and Female Power in India.” Women’s Studies International Forum 18.2 (1995): 125–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-5395(95)80049-U.

The Kavernacle. “Richard Dawkins and Anti-WOKE Atheists Are Now Becoming Christians.” YouTube, 4 April 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ZN25qxti-w.

———. “‘The Taliban Is BASED’ – Candace Owens, Nick Fuentes and Conservatives SIMP for the Taliban Takeover.” YouTube, 20 August 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bKje9wP8Cf0.

The Kavernacle [@TheKavernacle]. “I Love History, Obvs Did a History Degree, but the Way History Is Taught Is Not Good. Very Boring, Focuses on the Wrong Things and Most Importantly Extremely Western European Centric Which Helps Facilitate This Western Chauvinist Version of History.” Tweet. Twitter, 10 August 2022. https://x.com/TheKavernacle/status/1557081402948157444.

———. “The Only Reason We Still Know about Much of Ancient Greek Philosophy Is Because Muslims Preserved It and Let European Monks Translate Them (Mainly in Iberia). But from Europes Version of History You Get People Legit Justifying the Crusades as Something Noble.” Tweet. Twitter, 10 August 2022. https://x.com/TheKavernacle/status/1557081407171739651.

tommycahil1995. “From My Masters Prof….” Reddit Comment. R/BreadTube, 22 March 2019. www.reddit.com/r/BreadTube/comments/b3y0md/how_the_chinataiwan_dispute_could_cause_world_war/ej381w5/.

———. “Summary: When We Thi….” Reddit Comment. R/BreadTube, 22 March 2019. www.reddit.com/r/BreadTube/comments/b3y0md/how_the_chinataiwan_dispute_could_cause_world_war/ej2y4hq/.

Vööbus, A. “English Versions.” The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised. Edited by Geoffrey W. Bromiley, D. M. Beegle, and W. M. Smith. Grand Rapid, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1979.

Watkins, Carl. History and the Supernatural in Medieval England. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511496257.

Zechenter, Elizabeth M. “In the Name of Culture: Cultural Relativism and the Abuse of the Individual.” Journal of Anthropological Research 53.3, (1997): 319–47.

1735: 9 George 2 c.5: The Witchcraft Act, 2016. https://statutes.org.uk/site/the-statutes/eighteenth-century/1735-9-george-2-c-5-the-witchcraft-act/.

“Dawkins: I’m a Cultural Christian,” 10 December 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/politics/7136682.stm.

“Richard Dawkins Explains ‘The God Delusion.’” Fresh Air Archive: Interviews with Terry Gross. NPR, 28 March 2007. https://freshairarchive.org/segments/richard-dawkins-explains-god-delusion.

- The Kavernacle is wrong about the transmission of Greek philosophy to Europe.

- The Kavernacle is wrong about the scientific development of Europe & the Muslim world.

- The Kavernacle is wrong about English Bible translations.

- The Kavernacle is wrong about the British ban on the Hindu practice of satI.

The Kavernacle is wrong about the transmission of Greek philosophy to Europe

Here’s a tweet Kav posted which contains some bad history.

The only reason we still know about much of Ancient Greek philosophy is because Muslims preserved it and let European monks translate them (mainly in Iberia). But from Europes version of history you get people legit justifying the Crusades as something noble

The Kavernacle [@TheKavernacle], Tweet, Twitter, 10 August 2022

That’s a pop history myth. Firstly Greek texts reached Muslim hands when the Muslims conquered Christian territory, took manuscripts from Christian libraries and monasteries, and placed them in their own collections, very much a British Museum kind of situation. Secondly Arab and Persian leaders, who were not always Muslim, then hired translators who were overwhelmingly Christian to render the texts in Arabic, since the Arabs and Persians could not read Greek. Thirdly, many Greek and Latin texts were still preserved in both Rome and Constantinople, which is why Western scholars visited both locations to restore texts which were previously lost to them.

Historian of philosophy Cristina D’Ancona says “At the end of the fifth century and during the sixth, within a Christian environment both in Alexandria and in Athens, the Neoplatonic schools continued to comment upon Aristotle and Plato”.1

In fact the restoration of the Greek classics started in sixth century Western Europe with Boethius’ translations of Aristotle’s treatises on logic and his adaptations of various other works on logic and rhetoric. Grant says “Boethius’s importance for the early Middle Ages was immense”, adding “With a reasonable knowledge of Greek, he translated a number of Greek works into Latin and was thereby instrumental in preserving and making available numerous works that would otherwise have been unknown in the West”.2 Other significant contributers were Isidore of Seville, also in the sixth century, and Alcuin of York in the ninth century. Additional important translation efforts in Western Europe took place in the ninth, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article explains that even though there was a scarcity of primary Greek philosophical texts in the West, knowledge of Greek philosophy had also been preserved in Christian philosophical commentaries on Plato and Aristotle, written by theologians such as Tertullian, Victorinus, Ambrose, Themistius, Ammonius, Simplicius of Cilicia, Boethius, and John Philoponus. Consequently, the article comments “it is also important to recognize that the medievals knew a good deal about Greek philosophy anyway”.3

By the time Arabic translations of Aristotle were available to Western scholars, they had already recovered almost all of Aristotle, and most of the available classical Greek literature. Only a minority of the classical literature found its way to the West through a translation from Arabic. Historian of philosophy Frederick Copleston wrote that modern research into the transmission of Aristotle in particular has shown “translations from the Greek generally preceded translations from the Arabic”, and “it can no longer be said that the mediaevals had no real knowledge of Aristotle”.4

If you’re looking for more evidence than I’ve already cited here, I’ve already made six separate videos on the history of the Islamic Golden Age and the various myths surrounding it. You can find the playlist here, and the most relevant videos for this topic here and here.

The Kavernacle is wrong about the scientific development of Europe & the Muslim world

Here’s another tweet Kav posted which contains some bad history.

Like, this person was saying, the West has reached some sort of enlightenment through Jews and Christians, like, debating scientific discoveries. Not that, especially in the medieval time, Islamic societies were better for a lot of this stuff than, uh, Christian ones, which were actually, like, completely wrapped up in Christian superstition.

The Kavernacle, “Richard Dawkins and Anti-WOKE Atheists Are Now Becoming Christians,” YouTube, 4 April 2024

There is a lot of pop history myth here, though there is a grain of truth, and the Islamic Golden Age is rightly described as such. The medieval period began with the fall of Rome and its aftermath, around 476-500 CE. The Islamic Golden Age itself didn’t start until about 200 years later at around 750 CE, and it was inspired by the Greek texts captured during the Muslim conquests of Egypt and the Levant in the seventh century. But the Islamic Golden Age died out in the thirteenth century, two centuries before the end of the medieval period.

Briefly put, from the ninth to the twelfth centuries the Muslim world was ahead of Western Europe in various subjects such as mathematics, optics, and alchemy, while Western Europe was ahead in other subjects, such as anatomy, astronomy, and physics. However, by the end of the medieval period in the fourteenth century, Western Europe had advanced beyond the Muslim world in all of these fields.

During the Islamic Golden Age, the Muslim world did enjoy several intellectual advantages over Europe, such as in mathematics, in particular with the invention of complex algebra in the ninth century by the Persian mathematician Al-Khwarizmi, and they were ahead in alchemy, which Arab and Persian scholars developed to a new degree, drawing knowledge from earlier Greek and Byzantine works which had only a primitive understanding of what we would call chemistry. In some cases Western scholars such as Adelard of Bath, in the twelfth century, even traveled to Muslim lands, seeking out Arabic texts on a range of academic subjects, specifically with the intention of translating them into Latin so European scholars could learn from them.

First I’ll address the complex issue of what it means for either medieval Europe or the medieval Muslim world to be “better at thist stuff”, and then I’ll demonstrate medieval Europe was not “completely wrapped up in Christian superstition”.

Was medieval Europe or the medieval Muslim world better at “better at this stuff”?

I have written and edited this section several times now, attempting to address Kav’s question of whether medieval Europe or the medieval Muslim world was better at “better at this stuff” in a meaningful way, and concluded that the question is both ambiguous and wrongly founded on the false assumption that both regions had a monolithic character.

When Kav says medieval Islamic societies were “better at this stuff”, does he mean the “debating scientific discoveries”, or does he mean making scientific discoveries, or something else? I am not very sure, so I will first address the question of which was better at “debating scientific discoveries”, and then the question of which was better at making scientific discoveries.

Was medieval Europe or the medieval Muslim world better at “debating scientific discoveries”?

In both medieval Europe and the medieval Muslim world, both the quality of “debating scientific discoveries” and the extent to which this was possible, differed greatly from one region to another and one time period to another. Neither of these two intellectual worlds existed as a monolith, with considerable variation across time and place in both regions. Such debates were better in some parts of Europe and at certain times, and worse at others. Likewise, such debates were better in some parts of the Muslim world and at certain times, and worse at others. This depended entirely on the socio-cultural context in a given time at a given place.

How mathematical & scientific knowledge differed between medieval Western Europe & the medieval Muslim world

It is extremely difficult to assess whether medieval Western Europe or the medieval Muslim world was better at actually making scientific discoveries. Significant scientific progress was made in both regions during the medieval period, and these discoveries depended on factors which were constantly changing in both places, especially access to previous Greek knowledge, the ability to exchange scholarly knowledge between Europe and the Muslim world, and the support of local socio-economic and religious elites who sponsored and promoted intellectual endeavors. It can certainly be said that in both regions the greatest advances took place when all three of these factors coincided.

From the ninth to the twelfth centuries, the Muslim world was ahead of Western Europe in mathematics, optics, and alchemy, while Western Europe was ahead in anatomy, astronomy, and physics. However, by the fourteenth century Western Europe had advanced beyond the Muslim world in all of these fields.

In the twelfth century European scholars were well aware of how far ahead the Muslims were in mathematics. Charles Burnett, History of Islamic Influences in Europe of the Warburg Institute, says “Stephen the Philosopher lamented the poor knowledge of geometry among the Latins, and John of Salisbury reckoned that the only place where the study flourished was in (Islamic) Spain”.5

Likewise, sociologist Toby Huff writes “Just how far advanced the Arabs were in the field of mathematics has recently been stressed by Roshdi Rashed”, adding “Arab mathematicians in the eleventh and twelfth centuries achieved mathematical innovations that were not accomplished by Europeans until the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries”.6 But in the thirteenth century the situation changed dramatically. The so-called Oxford Calculators, a group of mathematicians at Oxford University, produced a range of significant mathematical advances.7

Alchemy was brought to Western Europe through Arabic texts. Principe writes “Alchemy, we are told, arrived in Latin Europe on a Friday, the eleventh of February, 1144”, explaining that it was on this day that the English monk Robert of Chester translated an Arabic work on alchemy, into Latin because, in Roberts words, “our Latin world does not yet know what alchemy is and what its composition is”.8

The history of alchemy in Western Europe therefore, starts with knowledge learned from Arab scholars in the Muslim world. Consequently, Principe says “Thus when alchemy arrived in medieval Europe, it came as an Arabic science, its lineage signaled by the Arabic definite article al- affixed to the word itself”, adding “It was thereafter in Europe that alchemy saw its greatest flowering and largest following”.9

It is certainly a fact that Western European scholars considered the Arabs to be not only the originators but also the masters of alchemy. For a century, Arabic works on alchemy were sought out, translated, and distributed throughout Europe. Almost the entire Western alchemical vocabulary was borrowed directly from Arabic, as Arabic alchemical terms were adopted by Western scholars directly without translation.10 Arab alchemists were so greatly respected and admired that some Western scholars even wrote their own works on alchemy under false Arabic names, in order to give them an air of authority which even a Latin name could not command.

However, European alchemy quickly overtook Muslim knowledge of the subject. One hundred years later, in the early thirteenth century, Western borrowing from Arabic alchemy had reached its peak. During the thirteenth century, Western alchemy started to break with the Arabic tradition. Western scholars were now writing their own works on alchemy, and were no longer interested in simply borrowing and systematizing earlier Arab findings. Princip says that it was at this time that “The translation of Arabic alchemical works dwindled to a trickle”, adding “By that time, Latin authors had begun writing their own books on alchemia”.11

As mentioned previously, it was around this time that the Western recovery of Aristotle and the rest of the classical Greek canon was virtually complete, and European scholars were turning their attention from Arabic sources, to the newly available Greek sources which, in many cases, they considered to be superior. The influence of Arabic alchemy on Western science started to decline significantly at this point. Western scholars used the new ideas they found in Aristotle and other works, and challenged both their own previous alchemical assumptions, and the alchemical knowledge they had learned from the Arabs.

Applying a more rigorous Aristotlelian approach, Western scholars started to break with the Arabic alchemical tradition. During the thirteenth century Paul of Taranto, an Italian Franciscan monk, started a new line of research which Western alchemists away from the Arabic legacy. Principle says “Undeniably, Paul’s works display the results of extensive practical testing and experimentation, and a level of rigor and theoretical synthesis rarely found in Arabic sources”, suggesting this may be due to quote “the Christian West’s taking more seriously Aristotle’s charge to discover the true natural causes of things than was widely the case in the Islamic world”.12

Three hundred years after Paul of Taranto had broken away from the Muslim alchemical legacy, Western alchemists had surpassed their Arabic teachers. Principe says “By the start of the sixteenth century, Latin alchemy had developed in many ways beyond the Arabic al-kīmiy‑’ Europe had acquired more than three centuries earlier”.13

The science of optics in the Muslim world was pioneered by Ibn Sahl, an Arab polymath whose work attempted to understand the physics of sight. His work compared and contrasted the views of Aristotle and Euclid, and concluded the Euclidean explanation was correct. Ibn Sahi’s work was influential on subsequent studies of optics in Western Europe. Persian mathematician al-Kindi made the next important contribution, writing on refraction and convex lenses in the tenth century, after studying Ptolemy’s book on optics.

However, the greatest progress in the Muslim world was made by Ibn al-Haytham, whose Book of Optics, written in the eleventh century, was of particular value, and remained the standard work on optics in the Muslim world for the next few centuries. Al-Haytham’s work also had an impact on European studies of optics, though it did not become available until the thirteenth century.

Robert McQuaid, of the Faculty of Optometry of Ramkhamhaeng University in Thailand, says that al-Haytham’s work “stimulated the study of optics within the nascent universities of Europe and provided a model to conduct experiments and influenced natural philosophers for centuries”.14 Hogendijk likewise says that al-Haytham’s work “was studied by many notable European scientists, such as Witelo, Roger Bacon, Leonardo da Vinci, Kepler, and Descartes”.15

There was clearly great potential for al-Haytham’s work to contribute directly to the Scientific Revolution, by explaining the science of optical lenses and enabling the invention of the telescope and microscope. However, contrary to expectation this did not happen. Given the advances in optics made by al-Haytham, it is surprising that their insights were not developed further in the Muslim world. Although Muslim scholars were deeply interested in identifying the properties of light and understanding the mechanics of vision, few of them studied lenses and how they functioned. Consequently, they never developed a complete understanding of the science of lenses, and therefore never invented either vision correcting spectacles, or the telescope.

In the early thirteenth century, the English bishop Robert Grosseteste drew new conclusions on the topic of optics. His work De Iride (On the Rainbow), explained how lenses could be used to improve vision, which enabled the invention of spectacles. Even more importantly, he also explained how lenses could be used to make a device to see things at great distances; a telescope. The first eyeglasses for the correction of vision defects were made by 1290.16

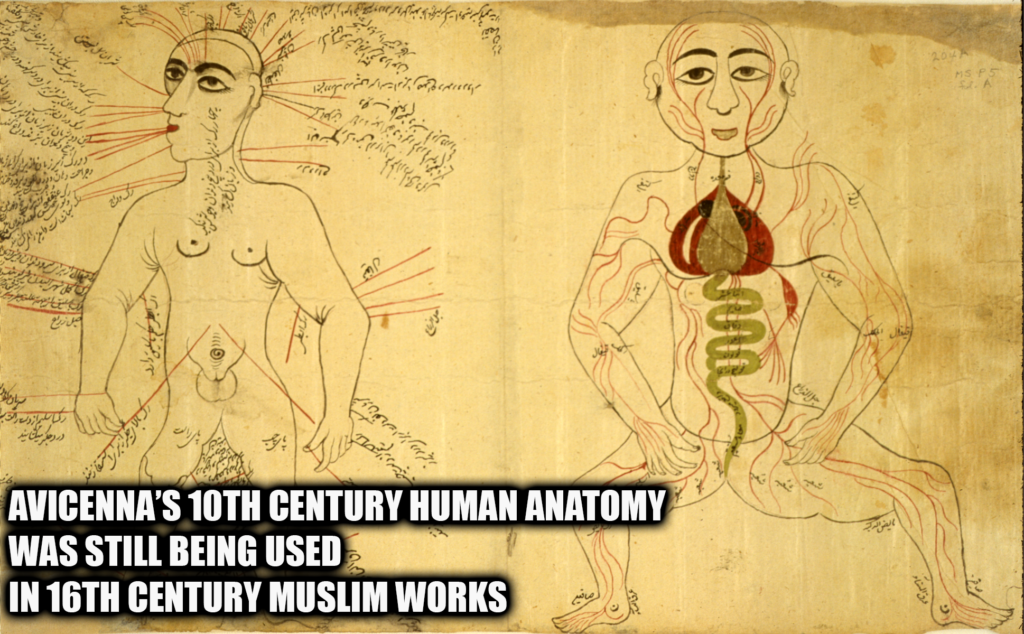

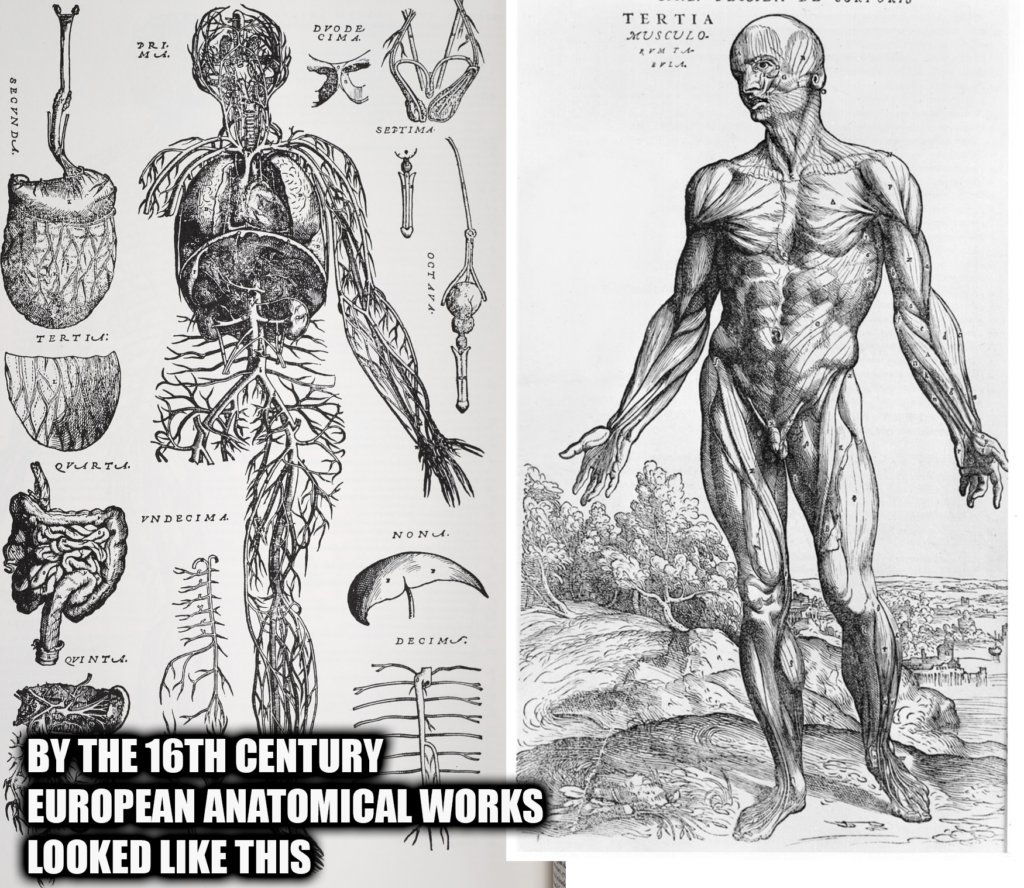

European medical knowledge also outstripped the Muslim world during this period. During the thirteenth century autopsies for the purpose of determining cause of death were legally required in Italy, and later human dissection for the study of anatomy re-appeared among Italian medical practitioners, as did human dissection for religious purposes.17 Consequently, Huff observes, “Europeans had considerable knowledge of human anatomy, not just that based on Galen and his animal dissections”.18

This was possible since European medical practitioners were able to dissect and experiment on pigs, which they already knew were far more accurate analogs for the human body than the monkeys used by the Roman physician Galen.19 Meanwhile, Muslim advances in anatomy were hindered by the fact that pigs were an unclean animal. As a result of their study of both human cadavers and pigs, Huff observes, Europeans “had a considerable stock of empirical knowledge about human anatomy that was not available in the Arab-Muslim world”, adding “European physicians engaged in a variety of practices that would have been forbidden in a Muslim context”.20

The difference this made to the development of medical knowledge in Europe can be seen very clearly in these two images.

Europe also remained ahead in astronomy overall, continuing to refine and ultimately challenge the Greek geocentric model of the solar system. Ultimately it was Copernicus who arrived at a heliocentric view of the solar system in the fifteenth century, while most Muslim astronomers continued to believe the sun orbited the earth for centuries after.21

It is true that Copernicus read Arabic and Persian scholars, but his heliocentric conclusions did not depend on them. Out of the five astronomers cited by Copernicus, al-Battani was not a Muslim and appears to have been a Sabean (a pre-Muslim traditional Arab religion), Thabit ibn-Qurra was definitely a Sabean, and al-Bitruji’s religious affiliation has similarly never been determined precisely, but he was not a Muslim. Regardless, although Copernicus cites them, he does not borrow from their work. In particular, although al-Bitruji disagreed with Ptolemy, his alternative astronomical model was less accurate than even Ptolemy’s, and was criticized for this by the later Jewish astronomer Levi ben Gersonides.

The two remaining astronomers cited by Copernicus are al-Zarqali, and Ibn Rushd. They were Muslims, but they both had a geocentric model of the solar system which differed significantly from the heliocentric model of Copernicus, and there is no evidence that Copernicus borrowed anything from them either. For further information on this, see Thony Christie’s article “A disservice to the history of Islamic Astronomy“.22

Important discoveries in physics were also made in medieval Europe by scholars such as John Philoponus, and Bonaventura, and although these were admired and studied in the Muslim world, in Europe they resulted in the scientific breakthroughs of Kepler, Galileo, and Newton.

Medieval Europe was not “completely wrapped up in Christian superstition“

The view of a universe guided and commanded by divine laws established in the beginning, was carried over from Jewish theology into the early Christian community, to which several writers are witness.23

One of the earliest Christian commentators to make this argument explicitly, was Athenagoras in the second century. Following and expanding the same reasoning as Sirach, Athenagoras differentiated between divine providence (God’s direct miraculous intervention in the world), and what he referred to as the ‘providential law of Reason’, the natural laws of the universe which God had established to govern all things.24 This was a critical distinction.

Two centuries after Athenagoras, Basil of Caesarea made the same argument for a universe given a divine command at creation, which it follows unerringly ever since.25 Basil’s work became highly influential in Christian discussions of the topic.26 The same theme was followed in the following centuries,27 and was developed further by Christian writers such as Augustine.28

The most significant result of this approach was a systematized understanding of the universe which laid the foundation for the Western scientific tradition. This understanding was revolutionary, and led directly to scientific breakthroughs of later centuries which earlier cultures (even the Greeks), had never come even close to. It provided a reliable and coherent framework within which the natural laws of the universe could be discovered, even if they were initially hidden.29

Most importantly, it provided clear evidence that even apparently blind, random, and unguided events, were in fact following faithfully the laws established by God at the creation. Augustine concluded that phenomena which appeared to happen by chance, were actually the product of divinely ordained laws which were simply as yet undiscovered.30

Application of this principle during the medieval era, was both a major contribution to the development of science, and a powerful correction of superstition. Like other pagan religions, the religion of Rome was obsessed with fortune telling; numerous signs, portents, and auguries were perceived in the stars and planets, in sacrifices to the gods, the weather, and the behaviour of animals. This superstitious attitude also produced credulous reports of supernatural events, which even some of Rome’s most intellectual, objective, and rational historians felt obligated to record.

For example, the Roman historian Livy (1st century BCE), despite his generally conservative and factual approach to his work, and despite his personal belief (as a Stoic), that the gods were distantly removed from human life, still made a point of recording the supernatural events and signs reported each year,31 without questioning whether or not they had actually happened.32 Even with the most generous assessment of probability, only two of these events (the comet and the rain of blood),33 could be considered remotely historical. Livy’s record of the typical Roman response to such reports, illustrates the extent of their superstition.34

In contrast, the Christian community of the first three centuries was disinterested in such events, except when its members were already influenced heavily by pagan writers or by their own pagan background. In the medieval era (from the 5th century), Christian leaders throughout the disintegrated Roman empire experienced great difficulty overcoming the pagan beliefs of their new converts, beliefs which in many cases were more suppressed than abandoned. Archbishop Isidore of Seville (6th century), showed great credulity in accepting the writings of earlier Greek and Roman authors who spoke of mythical animals and supernatural portents (which Isidore attempted to harmonize with Christianity).

Additionally, even some reasonably educated Christians (such as the literate monks who were the historians of the era), retained the superstitions of their original culture and religion. Consequently, they had a tendency to interpret a wide range of natural phenomena as indicative of supernatural events or signs from God.35 In particular, certain events were attributed to supernatural evil, such as evil spirits, demons, and witches.36

However, Christian theology (in particular the understanding of a universe ordered by God according to divinely established natural laws), exercised a powerful restraint on these interpretations. Consequently, the late medieval Christian chroniclers were far less likely than their earlier Greek and Roman counterparts, to even record such events.37 Although Livy had recorded eight portents in a single year, the Christian chronicler of the reign of Henry V (fourteenth century), recorded just two events in three and a half years.38

In the fifteenth century, another Christian chronicler recorded a falling star observed on a battlefield, noting “concerning its significance, men said many things”. However, considering such knowledge to belong only to God, the chronicler himself deliberately refrained from commenting, saying it would be blasphemy to attempt an interpretation of what the event might signify.39

The understanding of the universe governed by natural laws established by God, also exercised a powerful restraint on belief in supernatural evil, particularly in the form of witchcraft and magic. In the ninth century, archbishop Abogard of Lyons made a powerful effort to eliminate belief in ‘storm makers’, people who supposedly had the ability to conjure thunderstorms and hail. Abogard viewed such beliefs as both ignorant and contrary to Scripture,40 arguing that only God had the ability to command the elements He had created, and that He would never delegate such authority to wicked people for evil purposes.41

Significantly, Agobard quoted Sirach in Ecclesiasticus, using Sirach’s argument that God had established natural laws at the creation, as part of his own argument that disruption of these laws by merely human agency was impossible.42 For Agobard, the fact that God had established such laws meant it was impossible for them to be changed by anyone other than God Himself.

With the repeated reinforcement of this understanding of divinely ordained natural laws, superstitious explanations became discredited, and belief in supernatural wonders and portents was seen as a product of ignorance of the natural causes of phenomena.43 During the twelfth century a number of writers used the principle of natural law to debunk claims for supernatural events and encourage a rational view of the world.

The Christian philosopher Adelard of Bath wrote that superstitious amazement at observable phenomena was the result of considering an event while being ignorant of its true cause.44 When his nephew attributed the growth of plants from the earth to the direct involvement of God, Adelard corrected him and explained it was the result of a divinely ordained natural process.45

Adelard then taught his nephew that since the universe had been ordered accordingly to divinely established laws at the creation, phenomena observed in nature should be understood to have natural causes. Consequently, observers should always assume a natural cause as the primary cause, instead of attributing everything to God.46

Archbishop Eustathius of Thessalonica gave an explanation of blood rain (a portent reported frequently in the medieval era), which, though scientifically inaccurate, still treated the event as a natural phenomenon. His belief that it was blood which had evaporated from battlefields and returned to the earth as rain (a view found in early scholarly commentary on Homer’s Illiad), demonstrated a knowledge of the precipitation cycle and a preference for explaining apparently supernatural phenomena with natural causes.47

The Christian philosopher poet Bernard of Tours (also known as ‘Bernard Silvestris’), strongly encouraged the investigation of nature, believing that although its laws were hidden, it was possible for them to be sought out and discovered.48

Archdeacon Gerald of Wales, made the same application of the principle of natural law, correcting those who claimed that the leaping of the salmon was a supernatural event, and debunking claims that groaning sounds coming from a lake in winter, were miraculous.49 For Gerald, the fact that God had established natural laws for the operation of the universe, meant that those laws should be understood as the most likely cause for observable phenomena. This led him to consider natural causes for phenomena first, and to reject supernatural explanations based on superstition and ignorance.

Christian philosopher William of Conches likewise considered it unnecessary (and even impious), to attribute all observable phenomena directly to God as the primary cause; rather, they should be attributed to the natural laws established by God at creation.50

William experienced some opposition to his views. There were priests who saw no value in investigation of the natural world, and who believed nothing should be considered or investigated if it was not taught directly in Scripture.51 William dismissed this, arguing that Scripture was the wrong tool for investigating natural phenomena.52

Taking the same approach held by Christians all the way back to Augustine eight hundred years earlier (an approach which would later be used by Galileo), William argued that the Bible was silent on scientific matters, because they were not relevant to the Bible’s main focus, which was the gospel.53 He also took great exception to the priests who opposed investigation of the natural world, and objected strongly to their view that people should just hold a simple faith, believing whatever they were told.54

The Kavernacle is wrong about English Bible translations

Here’s another tweet Kav posted which contains some bad history.

You weren’t even allowed to write the Bible in English, by the way. For a long, long time. A guy called John Wycliffe was the first guy to try and do this. So the masses could actually read the Bible, because back in medieval England, only the elite and the church and people who could read Latin and Greek, they were the only ones allowed to.

The Kavernacle, “Richard Dawkins and Anti-WOKE Atheists Are Now Becoming Christians,” YouTube, 4 April 2024

Translations of various books of the Bible into the language of the common people, initially as paraphrase and poetry, had been written for nearly seven hundred years before Wycliffe was even born. The earliest of these were in Old English, also known as Anglo-Saxon, and later translations were in Middle English, from the twelfth century onwards.

- Seventh century Anglo-Saxon renderings into oral poetry by Caedmon.

- Eighth century translations of Psalms by Aldhelm.

- Eighth century translations of John’s gospel by Bede.

- Ninth century translations of Psalms & other passages by or for Alfred the Great.

- Tenth century translation of the Gospels, the Wessex Gospels.

- Eleventh century translation of portions of the Hexateuch by Aelfric.

- Twelfth century translation of Gospels & Acts by Orm.

- Thirteenth century translations of Genesis, Exodus, & Psalms.

- Fourteenth century translations of Psalms & New Testament books.

This is all readily available information, and can be found in a range of academic sources.55

The Kavernacle is wrong about the British ban on the Hindu practice of suttee

Now let’s look at a historical claim Kav made in his 20 August 2021 video “The Taliban Is BASED’ – Candace Owens, Nick Fuentes and Conservatives SIMP for the Taliban.

Now the history of using women’s rights saving women from the barbary of the east, of the Orient, has long been established in Western colonialism. … when the East India Company was taking over India, and this is before formal control by the British government, a governor general called Lord William Bentinck banned sati on December 4th 1829.

The Kavernacle, “‘The Taliban Is BASED’ – Candace Owens, Nick Fuentes and Conservatives SIMP for the Taliban Takeover,” YouTube, 20 August 2021

This is true, but it is very misleading since Kavis omitting around 30 years of important history prior to this point. Instead he represents the British as having imposed this ban instantaneously, without making any attempt to cooperate with or empower the Indian reformers who had arleady been attempting to eradicate the practice, saying this.

Of course it had a similar impact to the Afghanistan stuff, because there were lots of people in India at the time who wanted to ban it, even going as far back as hundreds of years before, and rather than empowering the reformers, the British just went in and banned it themselves, and of course that created the backlash of a foreign power from thousands of miles away coming to a country and enacting its own laws on the people, and not helping something organically grow, which if it grows organically then it will take root further.

The Kavernacle, “‘The Taliban Is BASED’ – Candace Owens, Nick Fuentes and Conservatives SIMP for the Taliban Takeover,” YouTube, 20 August 2021

The historical account Kav provides here is simply untrue.

Now in this particular case Kav cites a source for his claims, which is great, and not only that it’s a very good source, an article on the website The Victorian Web. This is not a formal academic site, but it does have a formal editorial process, and the editors and writers are scholars. The article on which Kav relies, entitled Cultural Imperialism or Rescue? The British and Suttee, was written by Jacqueline Banerjee, editor-in-chief of the website, and extremely qualified, with a relevant PhD and a lengthy list of scholarly publications in Victorian studies. Her article is long, detailed, well cited, and has a list of at least 28 sources.

However, it seems to me that Kav hasn’t read the article sufficiently closely, and has relied too greatly on this article. I’ll describe the historical facts here, and explain how I think Kav has misread Banarjee’s article.

When the British, when the British first entered India, they weren’t concerned with issues like suttee. In contrast, local activists and certain local leaders petitioned the British for intervention and aid in trying to stamp out suttee, believing they could harness the authority and power of the British in their struggle. Despite this, the British refrained from involvement in the issue for years. Historian Nancy G. Cassels says “the efforts of these reformists were offset by what amounted to a determined indifference on the part of the East India Company to all aspects of Indian society”, adding “At the turn of the century the practice of suttee was well protected by the Company’s policy of noninterference with native “religious usages and institutions” established in 1772″ 56

In 1798 the British placed a conditional ban on suttee,57 and after further pressure from local Indian reformist groups, between 1813 and 1829 the British attempted to regulate suttee with additional moderate legislation, differentiating between sortie committed with consent and sortie committed without consent.58 So the British attempted to moderate or regulate suttee for at least 10 years without banning it outright, even though all thier efforts were largely unsuccessful.

Indian journalist Rakhi Bose notes.

In fact, this attitude of the British to accommodate the practice by legislating it on the basis of individual will is often seen by historians as a way to pander to the political Hindu elite in the country, whose support was important to the crown’s stability in its Indian territories.

Rakhi Bose, “Dear Amish Tripathi, You’re Wrong. Sati Was Never Just a ‘Minor Practice’ in India,” News18, 31 October 2018

They just didn’t think it was an issue that they had any responsibility for. So in actual fact, there were people, local activists, local people on the ground, who were trying already to stamp out the practice, and who believed that they could harness the authority and power of the British in their struggle.

Suttee could not just be abolished overnight. … despite the outrage of foreign observers, early responses to the problem by the British were feeble, and the practice continued under their watch.

Jacqueline Banerjee, “Cultural Imperialism or Rescue? The British and Suttee,” The Victorian Web, 26 July 2014

Indian and English historians alike agree that there was real anxiety that heavy-handed measures would offend Indian sensibilities (see Majumdar et al. 817-18), and particularly a fear “of Hindus and Muslims perceiving British rule as a threat to their religions” (Keay 428).

Jacqueline Banerjee, “Cultural Imperialism or Rescue? The British and Suttee,” The Victorian Web, 26 July 2014

Despite British professions of horror and the untiring efforts of enlightened Hindus, especially the Bengali reformer Rajah Rammohun Roy (1772-1833), it was not until December 1829 that a later Evangelically-inclined Governor-General, Lord William Bentinck, having surveyed his Indian officers first to test their reaction, finally made suttee illegal in his second year of office (see Peers).

Jacqueline Banerjee, “Cultural Imperialism or Rescue? The British and Suttee,” The Victorian Web, 26 July 2014

- “At the end of the fifth century and during the sixth, within a Christian environment both in Alexandria and in Athens, the Neoplatonic schools continued to comment upon Aristotle and Plato.”, Cristina D’Ancona, “Greek into Arabic: Neoplatonism in translation,” in The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy, ed. Peter Adamson and Richard C Taylor (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005), 16. ↩︎

- Edward Grant, God and Reason in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 40. ↩︎

- “Still, while it is important to emphasize this absence of primary texts of Greek philosophy in the Latin Middle Ages, it is also important to recognize that the medievals knew a good deal about Greek philosophy anyway. They got their information from (1) some of the Latin patristic authors, like Tertullian, Ambrose, and Boethius, who wrote before the knowledge of Greek effectively disappeared in the West, and who often discuss classical Greek doctrines in some detail; and (2) certain Latin pagan authors such as Cicero and Seneca, who give us (and gave the medievals) a great deal of information about Greek philosophy.”, Paul Vincent Spade et al., “Medieval Philosophy,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, Summer 2018. (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2018). ↩︎

- “As modern investigation has shown that translations from the Greek generally preceded translations from the Arabic, and that, even when the original translation from the Greek was incomplete, the Arabic-Latin version soon had to give place to a new and better translation from the Greek, it can no longer be said that the mediaevals had no real knowledge of Aristotle, but only a caricature of his doctrine, a picture distorted by the hand of Arabian philosophers.”, Frederick Copleston, A History of Philosophy (A&C Black, 1999), 207-208. ↩︎

- “Stephen the Philosopher lamented the poor knowledge of geometry among the Latins, and John of

Salisbury reckoned that the only place where the study flourished was in (Islamic) Spain. Thus, a pioneer

in the twelfth-century translating movement, Adelard of Bath, devoted a text to the description of the

seven liberal arts (his On the Same and the Different) but also made the first translation of the Elements

from Arabic.”, Charles Burnett, “Translation and Transmission of Greek and Islamic Science,” in The Cambridge History of Science. Vol. 2, ed. David C Lindberg (New York, NY: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013), 346. ↩︎ - “Just how far advanced the Arabs were in the field of mathematics has recently been stressed by Roshdi

Rashed. He has shown that Arab mathematicians in the eleventh and twelfth centuries achieved

mathematical innovations that were not accomplished by Europeans until the fifteenth and sixteenth

centuries.”, Toby E Huff, The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China and the West (Cambridge (GB):

Cambridge University Press, 2003), 51. ↩︎ - “In the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, a new calculatory tradition was developed by scholars studying physics in an Aristotelian tradition. Contrary to the calendric calculations, these studies were not based in monasteries but in the more secular environment of the universities. Scholars at Oxford (the Oxford Calculators) took the lead. They developed precise notions of velocity, acceleration, and other important concepts in mechanics, and showed how these concepts could be used in mathematical accounts of natural phenomena.”, Sven Ove Hansson and Sven Ove Hansson, eds., “Introduction,” in Technology and Mathematics: Philosophical and Historical Investigations (Springer, 2018), 4. ↩︎

- “Alchemy, we are told, arrived in Latin Europe on a Friday, the eleventh of February, 1144. That was the

day that Robert of Chester, an English monk at work in Spain, completed his translation from Arabic of a

book often given the title De compositione alchemiae (On the Composition of Alchemy). In his prologue,

Robert explains that he chose to translate an alchemical text “because our Latin world does not yet

know what alchemy is and what its composition is.”, Lawrence Principe, The Secrets of Alchemy (University of Chicago Press, 2013), 51. ↩︎ - “Thus when alchemy arrived in medieval Europe, it came as an Arabic science, its lineage signaled by the

Arabic definite article al- affixed to the word itself. It was thereafter in Europe that alchemy saw its

greatest flowering and largest following.”, Lawrence Principe, The Secrets of Alchemy (University of Chicago Press, 2013), 4. ↩︎ - The word alchemy itself from the Arabic al-chymia, alkaline from the Arabic al-qali, borax from the Arabic buraq, azurite from the Arabic lazaward, sodium from the Arabic suwwad, realgar (which is ruby sulfur), from the Arabic rahj al-gar, aniline from the Arabic annil, natron from the Arabic natroon, alcohol from the Arabic al-kohl, elixir from the Arabic al-iksir, alembic from the Arabic al-inbiq, and many others. ↩︎

- Lawrence Principe, The Secrets of Alchemy (University of Chicago Press, 2013), 44. ↩︎

- “Undeniably, Paul’s works display the results of extensive practical testing and experimentation, and a level of rigor and theoretical synthesis rarely found in Arabic sources. This difference may come from the Christian West’s taking more seriously Aristotle’s charge to discover the true natural causes of things than was widely the case in the Islamic world.”, Lawrence Principe, The Secrets of Alchemy (University of Chicago Press, 2013), 55. ↩︎

- Lawrence Principe, The Secrets of Alchemy (University of Chicago Press, 2013), 81. ↩︎

- Robert McQuaid Od, “Ibn Al-Haytham, the Arab Who Brought Greek Optics into Focus for Latin Europe,” Advances in Ophthalmology & Visual System 9.22 (2019): 44. ↩︎

- “The Optics was translated into Latin around 1200, and the first printed edition (by F. Risner) appeared in 1572. The work was studied by many notable European scientists, such as Witelo, Roger Bacon, Leonardo da Vinci, Kepler, and Descartes.”, J. P. Hogendijk, Ibn al-Haytham’s Completion of the Conics-Springer New York (1985). ↩︎

- Vincent Ilardi, Renaissance Vision from Spectacles to Telescopes (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2007), 6. ↩︎

- Katharine Park, “Myth 5: That the Medieval Church Prohibited Dissection,” in Galileo Goes to Jail: And Other Myths about Science and Religion, ed. Ronald L. Numbers (Harvard University Press, 2009), 43–49. ↩︎

- “Current scholarship reveals that Europeans had considerable knowledge of human anatomy, not just that based on Galen and his animal dissections. For the Europeans had performed significant numbers of human dissections, especially postmortem autopsies, during this era.”, Toby E Huff, The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China and the West (Cambridge (GB): Cambridge University Press, 2003), 195. ↩︎

- “But here one should note that already in the early twelfth century – a hundred years before Ibn al-Nafis – Europeans, above all in Salerno, were performing dissections of pigs. In one document that has come down to us, written before 1150, the author says, “Although some animals such as monkeys, are found to resemble ourselves in external form, there is none so like us internally as the pig, and for this reason we are about to conduct an anatomy upon this animal.” This early twelfth-century document was meant to be accompanied by an actual dissection.”, Toby E. Huff, Intellectual Curiosity and the Scientific Revolution: A Global Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2010), 178. ↩︎

- “It goes without saying that a Muslim physician would find operating on a pig highly repulsive. In short, by the thirteenth century there was no major ideological resistance to the performing of human dissections in Europe. At the time of Ibn al-Nafis, European anatomists were practicing dissections on the pig and also the human body. Consequently, they had a considerable stock of empirical knowledge about human anatomy that was not available in the Arab-Muslim world. Inspired by the pursuit of scientific knowledge, European physicians engaged in a variety of practices that would have been forbidden in a Muslim context.”, Toby E. Huff, Intellectual Curiosity and the Scientific Revolution: A Global Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2010), 178. ↩︎

- “Long after the Copernican Revolution, Islamic observational astronomy continued in the geocentric Ptolemaic tradition.”, S. Nomanul Haq and Massimo Campanini, “Astronomy,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Science, and Technology in Islam, ed. Salim Ayduz (Oxford University Press, 2014), 74. ↩︎

- Christie Thony, “A Disservice to the History of Islamic Astronomy,” The Renaissance Mathematicus, 1 May 2019, https://thonyc.wordpress.com/2019/05/01/4957/. ↩︎

- “Early Jewish and Christian theologians expressed this biblical idea using the Greek phrase for ‘law of nature’, nomos physeos. The suspension of the earth, the orbits of the sun, moon and stars, and the alternation of the seasons were all established in the beginning by God’s word and law.”, Professor Christopher B. Kaiser, Toward a Theology of Scientific Endeavour: The Descent of Science (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013), 49. ↩︎

- “The assimilation of Sirach’s idea of laws of nature into Christian theology can be seen as early [sic] Christian apologists like Athenagoras, who wrote a Plea on Behalf of Christians in the 170s: God’s particular providence [over heaven and earth] is directed toward the deserving, while everything else is subject to [God’s] providential law of Reason (nomo logou] according to the common nature of things…. Each part has its origin in Reason [gegonos logo], and hence none of them violates its appointed order. (Plea 25.2-3)”, Professor Christopher B. Kaiser, Toward a Theology of Scientific Endeavour: The Descent of Science (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013), 49. ↩︎

- “It is this command which, still at this day, is imposed on the earth and, in the course of each year, displays all the strength of its power to produce herbs, seeds, and trees. Like tops, which after the first impulse continue their evolutions, turning upon themselves, when once fixed in their center; thus nature, receiving the impulse of this first command, follows without interruption the course of ages until the consummation of all things.”, Basil of Caesarea, “The Hexaemeron,” 5.10, in St. Basil: Letters and Select Works, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, trans. Blomfield Jackson, vol. 8 of A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1895), 81. ↩︎

- “One of the most influential of these texts was Basil of Caesarea’s treatise ‘On the Six Days of Creation’ (In Hexaemeron), which we just discussed in connection with the idea of multiple universes and will take up again in Chapter 3.”, Professor Christopher B. Kaiser, Toward a Theology of Scientific Endeavour: The Descent of Science (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013), 49. ↩︎

- “Writing in the early fourth century, Eusebius of Caesarea (Palestine) compiled a rich variety of Greek and Jewish sources in his treatise on The Preparation for the Gospel (c. 315 CE). This massive work contains the first instance of the idea of ‘laws of universal nature’ in Christian literature.”, Professor Christopher B. Kaiser, Toward a Theology of Scientific Endeavour: The Descent of Science (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013), 158. ↩︎

- “In this passage Augustine makes explicit (as a commentary should) what Basil had only hinted at. Mathematical instructions (‘causal reasons’) are embedded in nature in such a way that their effects occur naturally in their proper time according to a predetermined sequence. In stating that these laws have a mathematical form, Augustine was combining the idea of laws in nature with the idea we traced earlier, that of creation in accordance with quantitative measure (based on Wisdom 11:20).”, Professor Christopher B. Kaiser, Toward a Theology of Scientific Endeavour: The Descent of Science (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013), 161. ↩︎

- “The result of this Latin synthesis was a prescientific concept of mathematical law that gave early modern scientists like Kepler confidence that the phenomena of nature obeyed fixed laws even if they did not conform to any known laws.”, Professor Christopher B. Kaiser, Toward a Theology of Scientific Endeavour: The Descent of Science (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013), 161. ↩︎

- “The point was made most memorable by Augustine in his reflections on a verse of Psalm 148:8 fire and hail, snow and frost, stormy wind fulfilling God’s command: Nothing seems to be so much driven by chance as the turbulence and storms by which these lower regions of the heavens…. are assaulted and buffeted. But when the Psalmist added the phrase, fulfilling his command [Ps. 148.8], he made it quite clear that the plan in these phenomenon subject to God’s command is hidden from us rather than that it is lacking to universal nature. (On Genesis Word for Word V. 42)”, Professor Christopher B. Kaiser, Toward a Theology of Scientific Endeavour: The Descent of Science (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013), 161. ↩︎

- “Generally speaking, Livy contents himself with recording auguries, portents, and propitiations in a straightforward and laconic style, making no comment of any kind about them.”, Marcia L. Colish, The Stoic Tradition from Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages, Volume 1. Stoicism in Classical Latin Literature, Studies in the History of Christian Traditions Ser (Boston: BRILL, 1990), 300. ↩︎

- “Livy then describes eight prodigies which had been reported that year, including a blazing comet, a talking cow, a rain of stones and one of blood, a palm which had ‘sprung up’ in the temple of Fortuna Primigenia, and a statue of Apollo that began to shed tears.”, Chris Given-Wilson, Chronicles: The Writing of History in Medieval England (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007), 22. ↩︎

- So called ‘blood rain’ is red coloured rain typically caused by iron oxide in atmospheric dust, trapped in raindrops. ↩︎

- “In view of these public portents, the Sacred [Sybilline] Books were consulted by the Board of Ten [the decemviri]; they officially announced the names of the gods to whom the consuls were to offer sacrifices with the greater victims; they also gave out that a day of public prayer should be observed, that all the magistrates should sacrifice the greater victims at all the seats of the gods, and that the people should wear wreaths.”, Carl Watkins, History and the Supernatural in Medieval England, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007). ↩︎

- “Almost any unusual event was capable of a portentous reading. Solar and lunar phenomena (comets, bloodmoons, meteors, eclipses) and adverse weather (thunderstorms, gales, floods, droughts) were the most common portents mentioned by chroniclers.”, Carl Watkins, History and the Supernatural in Medieval England, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007). ↩︎

- “Thus especially violent storms became associated with the works of demons. The Lanercost chronicler recounted cautionary tales illustrating that ‘it is evil spirits that stir up tempests’ and described how during a storm in the diocese of York people ‘had heard demons yelling in the air’.”, Carl Watkins, History and the Supernatural in Medieval England, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 58. ↩︎

- “In fact, with a few notable exceptions, late medieval English chroniclers did not record a large number of preternatural events in their chronicles. However, the way in which they inserted them, clearly indicate the significance with they attached to them, and to their interpretation.”, Chris Given-Wilson, Chronicles: The Writing of History in Medieval England (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007), 23. ↩︎

- “For example, the Gesta Henrici Quinti (‘Deeds of Henry V’), which was written by one of Henry V’s household chaplains and covers the first three and a half years of his reign, includes just two ‘auspicious’ events in a chronicle running to 180 pages in its most recent edition.”, Chris Given-Wilson, Chronicles: The Writing of History in Medieval England (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007), 23. ↩︎

- “But I who am writing, not wishing to blaspheme, leave what it foretold to God, the Creator of nature, and to the operation of the elements.”, “For example, the Gesta Henrici Quinti (‘Deeds of Henry V’), which was written by one of Henry V’s household chaplains and covers the first three and a half years of his reign, includes just two ‘auspicious’ events in a chronicle running to 180 pages in its most recent edition.”, Chris Given-Wilson, Chronicles: The Writing of History in Medieval England (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007), 23. ↩︎

- “In these regions, nearly all men, noble and common, city and country dwellers, old and young, believe that hail and thunder can be produced by human will. For as soon as they hear thunder and see lightning, they say ‘a gale has been raised’. When they are asked how the gale is raised, they answer (some of them ashamedly, with their consciences biting a little, but others confidently, in a manner customary to the ignorant) that the gale has been raised by the incantations of men called ‘storm-makers’, and it is called a ‘raised gale’ It is necessary that we examine by the authority of Holy Scripture whether it is true as the masses believe.”, Abogard, ‘On Hail and Thunder’, Lewis (trans., in 2007), from the Latin text in Agobardi Lugdunensis Opera omnia, ed. L. Van Acker, Corpus Christianorum (Turnholti [Turnhout, Belgium]: Typographi Brepols, 1981). ↩︎

- “Certainly Moses, the servant of God, was good and righteous, but these people do not dare to say that the so-called ‘storm-makers’ are good and righteous, but rather evil and unrighteous, deserving of both temporal and eternal condemnation, nor are they servants of God” except perhaps by circumstance rather than willing service.”, Abogard, ‘On Hail and Thunder’, Lewis (trans., in 2007), from the Latin text in Agobardi Lugdunensis Opera omnia, ed. L. Van Acker, Corpus Christianorum (Turnholti [Turnhout, Belgium]: Typographi Brepols, 1981). ↩︎

- “It says that all these things also grow quiet and are calmed at the command of God. Therefore no human assistant should be sought in such events, because none will be found, except perhaps the saints of God, who have brought about, and are yet to bring about, many things.”, Abogard, ‘On Hail and Thunder’, Lewis (trans., in 2007), from the Latin text in Agobardi Lugdunensis Opera omnia, ed. L. Van Acker, Corpus Christianorum (Turnholti [Turnhout, Belgium]: Typographi Brepols, 1981). ↩︎

- “By mid-twelfth century, wonders were thought to be a symptom of ignorance of causes and superstition;”, Zrinka Stahuljak, Thinking through Chrétien de Troyes, Gallica (Woodbridge (Suffolk, England)) (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2011), 95. ↩︎

- “According to Adelard of Bath (1116-1142), to marvel was to consider “effects in ignorance of their natural causes” (Daston and Park, p. 110)”, Zrinka Stahuljak, Thinking through Chrétien de Troyes, Gallica (Woodbridge (Suffolk, England)) (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2011), 95. ↩︎

- “In response to his nephew’s query about why plants rise from the earth, and the nephew’s conviction that this should be attributed to “the wonderful operation of the wonderful divine will,” Adelard replies that it is certainly “the will of the Creator that plants should rise from the earth. But this thing is not without a reason,” which prompts Adelard to offer a naturalistic explanation based on the four elements.”, Edward Grant, God and Reason in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 71. ↩︎

- “Adelard’s emphasis on the use of reason is rather remarkable. His message is clear. He firmly believed that God was the creator of the world, and that God provided the world with a rational structure and a capacity to operate by its own laws. In this well-ordered world, natural philosophers must always seek a rational explanation for phenomena. They must search for a natural cause and not resort to God, the ultimate cause of all things, unless the secondary cause seems unattainable.”, Edward Grant, God and Reason in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 72. ↩︎

- “The scholia on the Homeric passages (Scholia in Modem, ed. Dindorf and Maas, i. 374; Hi. 457-58; iv. 131; v. 381) suggest that after great battles blood flows into the rivers, whence it is taken up into the clouds and descends in rain.The twelfth-century archbishop Eustathius gave much the same explanation (Commentarii, Leipzig, 1829, III, 336).”, John S. P. Tatlock, “Some Mediaeval Cases of Blood-Rain,” Classical Philology 9.4 (1914): 442. ↩︎

- “[Humanity] shall behold clearly principles shrouded in darkness, so that Nature may keep nothing undisclosed. He will survey the aerial realms, the shadowy stillness of Dis [the underworld], the vault of heaven, the breadth of the earth, [and] the depths of the sea. He will perceive whence things change, why the summer swelters, autumn blights the land, spring is balmy, winter cold. He will see why the sun in [sic] radiant, and the moon, why the earth trembles, and the ocean swells. Why the summer day draws out its long hours, and night is reduced to a brief interval…. (Cosmographia, Mircosmos [sic] 10)”, Professor Christopher B. Kaiser, Toward a Theology of Scientific Endeavour: The Descent of Science (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013), 175. ↩︎

- “The spectacle of leaping salmons in the rivers of Wales and Ireland was dissected in similar fashion, Gerald observing that this behaviour may seem hard to believe but it is from the nature (ex natura) of this fish to perform such feats. He was also reluctant to accept the beliefs of Welsh villagers who held that the groaning of a lake in winter was miraculous. Dismissing their claims, Gerald offered an alternative physical explanation, ascribing the noises to air trapped beneath its frozen surface and being violently released.”, Carl Watkins, History and the Supernatural in Medieval England, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 30. ↩︎

- “William thought it improper to invoke God’s omnipotence as an explanation for natural phenomena. Like all natural philosophers in the Middle Ages, William of Conches believed that God was the ultimate cause of everything, but, like Adelard of Bath, he believed that God had empowered nature to produce effects and that one should therefore seek the cause of those effects in nature.”, Edward Grant, God and Reason in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 73. ↩︎

- “Some priests believed only what they found in the Bible.”, Edward Grant, God and Reason in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 74. ↩︎

- “He also rejected the idea that Scripture was of use in natural philosophy.”, Edward Grant, God and Reason in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 74. ↩︎

- “when modern priests hear this, they ridicule it immediately because they do not find it in the Bible. They don’t realise that the authors of truth are silent on matters of natural philosophy, not because these matters are against the faith, but because they have little to do with the strengthening of such faith, which is what those authors are concerned with.”, Edward Grant, God and Reason in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 74. ↩︎

- “But modern priests do not want us to inquire into anything that isn’t in the Scriptures, only to believe simply, like peasants.”, Edward Grant, God and Reason in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 74. ↩︎

- “The need for translation into the vernacular arose, therefore, with the extensive evangelization and the growth of the Anglo-Saxon Church in the 6th century. The beginnings of this work seem to have come in the latter part of the 7th cent., not so much through precise translation of the Bible as through the rendering of portions of it into Anglo-Saxon poetry. … The Psalms had their usual appeal, and two versions in prose followed in the 14th century. One is from the Midlands, while the other is the famous translation by Richard Rolle of Hampole near Doncaster in the North. Rolle’s version was incorporated in a commentary and proved to be so successful that it was copied out in other dialects.”, A. Vööbus, “English Versions,” in The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised, ed. Geoffrey W. Bromiley, D. M. Beegle, and W. M. Smith (Grand Rapid, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1979), 83, 84. ↩︎

- “During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, however, the efforts of these reformists were offset by what amounted to a determined indifference on the part of the East India Company to all aspects of Indian society. At the turn of the century the practice of suttee was well protected by the Company’s policy of noninterference with native “religious usages and institutions” established in 1772.”, Nancy G. Cassels, “Bentinck: Humanitarian and Imperialist—the Abolition of Suttee,” Journal of British Studies 5.1 (1965): 77. ↩︎

- “The British first put a conditional ban on Sati way back in 1798 in Calcutta. It eventually tried to regulate Sati by allowing a selective number of self-immolation cases where the woman performing was seen to not be under any pressure and was, in fact, doing it with her own will.”, Rakhi Bose, “Dear Amish Tripathi, You’re Wrong. Sati Was Never Just a ‘Minor Practice’ in India,” News18, 31 October 2018. ↩︎

- “Between 1813 and 1829 the British attempted to regulate the performance of sati by ensuring it conformed to certain ‘scriptural’ standards. Key among these was that the rite was performed with the free consent of the widow, who should not, among other things, be less than 16 years of age, pregnant, intoxicated or the mother of very young children.”, Andrea Major, Sovereignty and Social Reform in India: British Colonialism and the Campaign against Sati, 1830-1860 (London: Routledge, 2014), 122. ↩︎